Ecological Dynamics and the Constraints Lead Approach to Skill Acquisition in Climbing

- The Science of Skill

- Ecological Dynamics

- Dynamics in Movement

- The Ecological Approach

- A self-indulgent aside for the Machine Learning student.

- Why Theorize?

- Skill Acquisition Theories in Climbing Culture

- The Constraints-Led Approach

- Self-organization and Learning

- CLA in climbing

- Applications

- Finding Opportunities for Skill Work

- High-Quality Setting

- Variety and letting go of “fundamentals”

- Future Directions

- Against being dogmatic

- CLA all the things

Climbing is a skill sport, and it’s widely accepted within the climbing community that developing skill should be the priority of any aspiring climber. But what is skill, and how does one go about developing it?

The Science of Skill

I made a few attempts at investigating what science had to say about these questions. For various reasons, many such attempts proved unsuccessful. I am only willing to spend so many hours digging through an ever-growing stack of research references.

Then, a few months ago I discovered the work of Rob Gray. Rob is a researcher and professor of skill acquisition. He’s also a skill acquisition specialist for professional athletes, most notably the Red Sox.

Luckily for those of us who are interested in the science of skill, Rob dedicates a lot of his time to communicating research to a general audience. He is the creator of the perception and action podcast, and has also written several books about skill acquisition. I first discovered Rob’s work through his podcast which I expediently consumed. I then read two of his books - How We Learn to Move and Learning to Optimize Movement.

I am really grateful for Rob’s work because he provides much needed context and framing to this field. He connects individual studies into narratives, explains the implications of significant findings, and points out conflicting evidence, open questions, and challenges when applying the science to actual sport. These are things that are really difficult to extract from reading research directly.

Most importantly, Rob has given me a framework for understanding skill development, which I have been able to apply to my own climbing training.

Ecological Dynamics

Rob’s work centers around the theory of ecological dynamics (ED). The dynamics in ED comes from Dynamical Systems Theory (DST) - a branch of mathematics.

DST is often used to study systems made of interacting components, where the relationship between the components can be specified, but the overall system is too complex to solve. One example is orbits of objects in space - where the gravitational forces between each pair of objects are known, but predicting the orbits of all of the objects is intractable (as in the famous Three Body Problem [ref]).

In his book, Rob uses the example of a flock of birds. We can describe the rules followed by each individual bird - say, to match the direction and speed of its neighbors, and to maintain a certain distance. However, we can’t predict the exact trajectory of all of the birds.

A flock of birds in an evening sky.

DST is concerned with studying the various properties of such systems, often through the use of simulations. How sensitive is the system to initial conditions? Are there stable points of equilibrium - called attractors - that the systems tend to evolve towards? Are there any invariants that we can observe about the system?

Dynamics in Movement

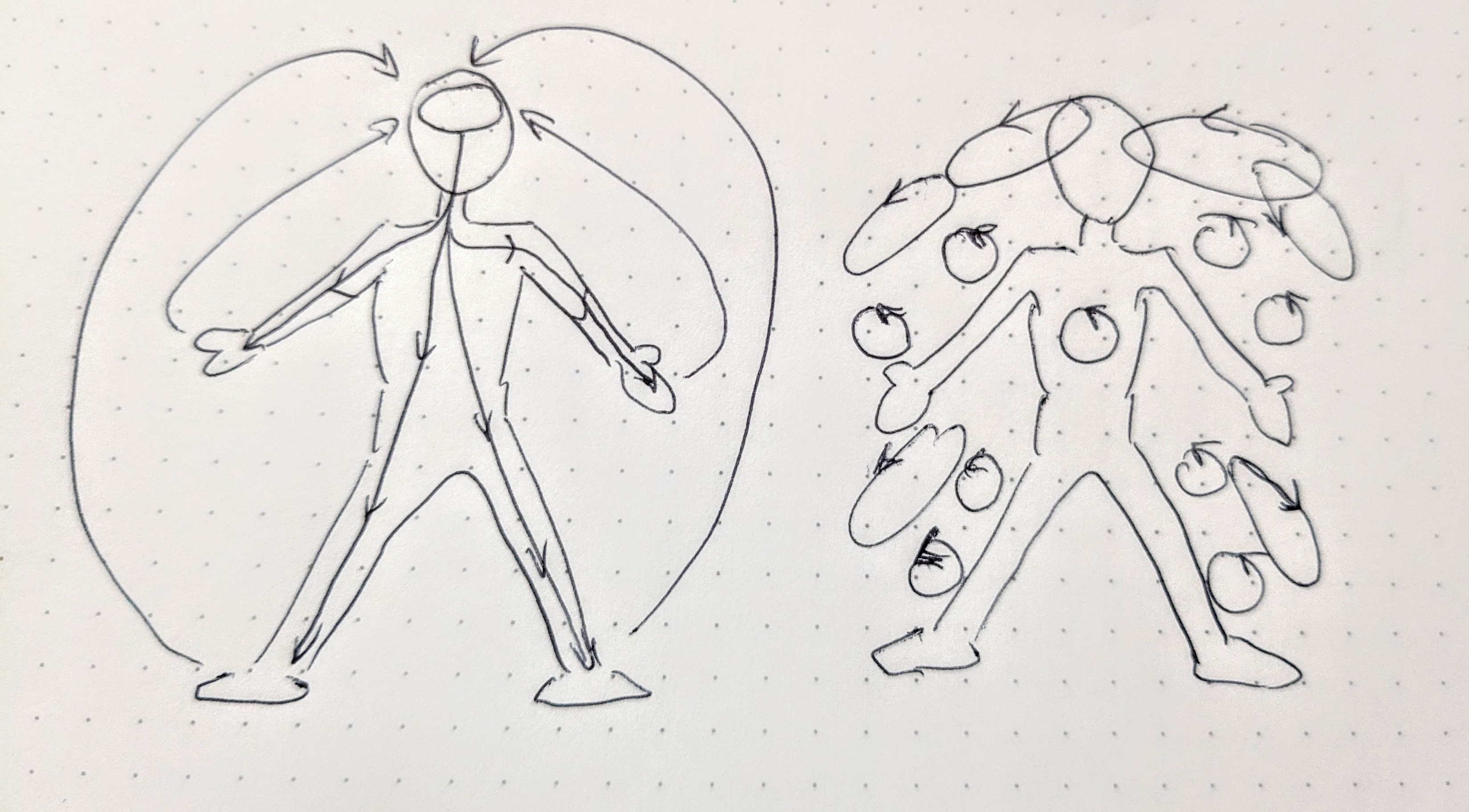

A common view of movement (illustrated below on the left) is that our brain takes in information from the environment, and then creates a movement plan. The brain then sends the plan to our muscles to execute - a top-down, one-directional process.

Traditional view illustrated on the left - a one-directional transfer of information from the senses to the brain to the muscles. ED view illustrated on the right - a distributed network of feedback loops between all of the various components of the body.

In contrast to this view, ED considers our body to be a dynamical system, made up of interacting components: the fascia, muscles, sensor organs, neurons, etc... All of these components are in continuous feedback loops - compensating and reacting to each other. ED challenges us to view movement as emerging from this distributed system - through a process called *self-organization *(emergent organization may be more accurate).

Consider the concept of “trusting your feet”. The ankle, knee and hip joint have to act in a coordinated way to keep the center of mass balanced over the foot. Within each muscle, the fibers need to fire in the appropriate sequence and frequency to maintain a consistent tension, and that tension must balance with the antagonist muscles and compensate for the stretching of the surrounding fascia, using continuous feedback from the various surrounding stretch receptors embedded in the muscles and fascia. All of this happens on top of the toe being able to provide consistent pressure to take advantage of the friction between the climbing shoe and the rock - using the various sensory information coming from the skin. Furthermore, this movement needs to be coordinated with the trunk and all of the other body parts.

A frequently observed consequence of self-organization is that it is really difficult to tell someone how to do a climbing move. You can describe the exact body position that the climber should have. You can show them a video of the move. You can even come up to the climber on the wall and manually try to arrange their body. However, none of this addresses the various feedback loops within the climbers body that have to adjust to perform the move. Instead, the climber has to explore their way through the movement until they feel it. And very often, the way they end up doing the move is unique to their particular body.

The Ecological Approach

The other part of ED is ecological - that is, having to do with the environment. In the “standing on your feet” example above, the sensory information from the skin of the foot is used to control the pressure the foot exerts on the hold. ED posits that sensory information from the environment is used in this way to directly drive movement at all levels within the system. Perception and action are coupled in a continuous feedback loop.

Because of this, a movement strategy is inseparable from the environment in which it is used. When you change the environment, you change the sensory signals that the body is receiving, and consequently the body needs to self-organize in a novel way.

Climbers who make the transition from the gym to the crag are intimately familiar with this phenomenon. Rock has a much broader variety of shapes and textures when compared to plastic. When we start climbing outside our body has to self-organize into novel coordinative structures in order to deal with this new variety of sensory information.

Another example every climber has encountered: You can do a dynamic move easily at ground level. However, when you encounter the same move near the top of a boulder, you suddenly can’t move dynamically at all. What’s happening here? From an ED lens, when you get scared, your body floods with all sorts of hormones. This throws your sensori-motor feedback loops out of whack, robbing you of all of your existing movement strategies.

A self-indulgent aside for the Machine Learning student.

I struggled with wrapping my head around self-organization. How can movement - which feels so intentional, arise as an emergent property of a dynamical system? Having studied machine learning, I tried to reconcile this idea with my knowledge of neural networks, and things I learned about the animal visual cortex.

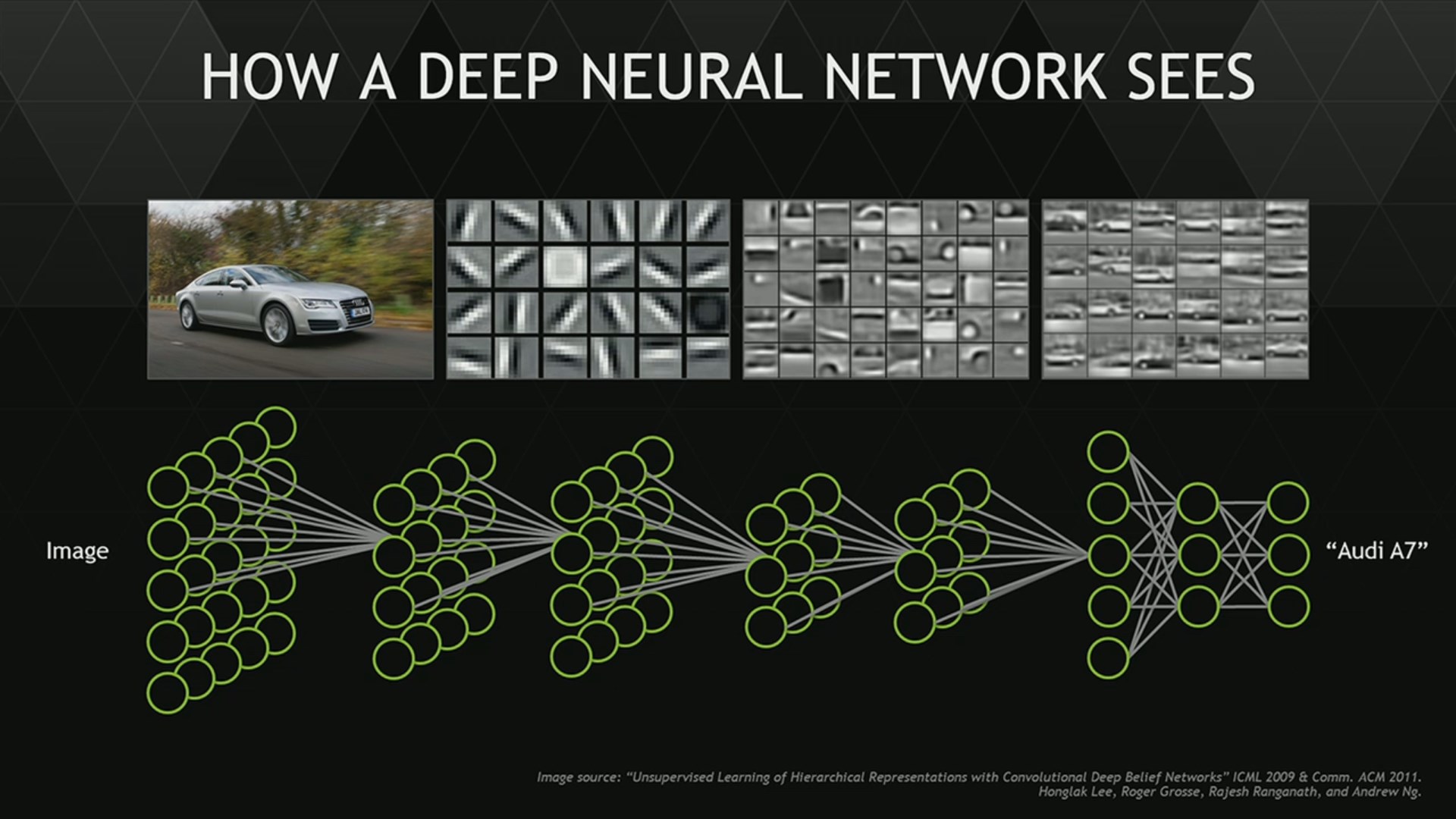

An image of a neural network. On the left, a large number of neurons read pixel data from the image. As we go from left to right, we travel through several layers of neurons. Each neuron is connected to many neurons in the preceding layer.

Above the neural network, a series of images is shown, demonstrating some examples of the images that neurons at that layer are most responsive to.

This starts with simple edges in the first image, pictures of circles and lines in the second, and finally full images of cars in the last image.

Image source: “Unsupervised Learning of Hierarchical Representations with Convolutional Deep Belief Networks” ICML 2009 & Comm. ACM 2011. Honglak Lee, Roger Grosse, Rajesh Ranganath and Andrew Ng.

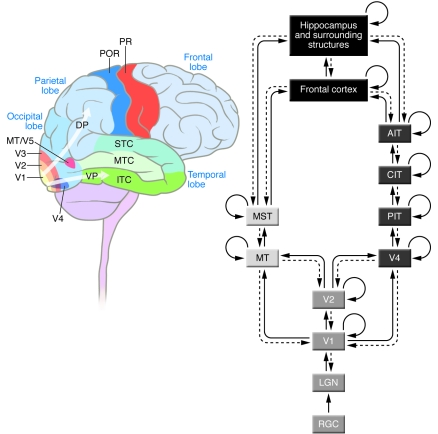

An image of the human brain, with various areas highlighted. The visual cortex layers start with V1 in the very back of the head where it is connected to the retina, and radially progress to V2, V3, V4 and V5 from there.

Image from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2929717/

Deep neural networks and the visual cortex are organized in layers. On the one end are the neurons that receive information from the environment. This is the left-most layer in the neural network in the left image, receiving the information about the color of each pixel. Within human brains, these are the neurons that receive information from our eyes. The information then travels to deeper layers of the network.

One way we can make sense of what’s happening in a neural network is to pick a neuron and ask “what image makes this neuron light up the most?”. The neurons from superficial layers respond to simpler visual properties like edges and bright or dark spots. Layers a bit deeper down respond to more complex shapes like circles and lines. Deeper than that, neurons seem to light up for categories of objects, like images of cars.

Similar things were discovered when looking at the visual cortex of animals - the shallower layers respond to local features like edges, while deeper layers respond to more abstract properties of the image. Another interesting observation about the visual cortex is that the neurons at the higher levels of processing are connected to higher-level processes in the rest of the brain, like attention [ref].

Thinking of the sensorimotor system in this layered way helps me make sense of self-organization. There are shallow pathways between senses and muscles that encode simple coordinative structures - like reflexes, maintaining muscle tone, agonist/antagonist couplings. Deeper pathways may be responsible for behaviors like stabilizing joints. Deeper still would be structures that control multi-joint or inter-limb coordination. (I am not 100% that this is correct, but I think it’s a reasonable interpretation of e.g. [ref]).

Conscious processes like goal setting, attention and intention are connected to the deepest parts of our sensorimotor pathways, but the act of moving happens through the simultaneous interplay of all layers - emergent organization.

(It’s interesting to think about our experience of movement from this point of view. When I reach to pick up an object, is it the conscious intent that drives the movement? Or does the conscious awareness arise simultaneously with the movement?)

(Also, I think it is worth mentioning that even though it is convenient to assign semantic meaning to various neurons, like “this neuron detects cats”, or “this pathway stabilizes the shoulder joint”, this is just our own imposition. Neurons are just connecting and processing information in a way that doesn’t necessarily align with any conceptual model. The behavior of neurons often cannot be summarized in any meaningful way, and many neurons participate in ambiguous ways with many unrelated concepts [ref].)

Why Theorize?

This may seem like a lot of work that leads to fairly self-evident things. Climbers need to get a feel for movement. Skills don’t necessarily transfer between different environments. What have we gained from this?

One of the things Rob is fond of saying is that when we try to improve our skills, we are always operating with an underlying theory, even if we don’t explicitly state it (or maybe aren’t even aware of it). I think there is a prevalent theory of skill development within climbing, and in many ways it sits at odds with ED.

Skill Acquisition Theories in Climbing Culture

My first experience with skill training in climbing centered around “footwork” - an often-emphasized fundamental. A common recommendation for developing footwork at the time (15 years ago?) was a drill called “silent feet”, where one would pick a climb a bit below their flash level and climb it without making any noise with their feet.

I drilled silent feet a lot (months? years?). I got pretty good at it. My climbing didn’t really change. Looking back at it through the lens of ED, that’s not particularly surprising.

First, what are the dynamics of silent feet? Typically, the climber is standing on a foot, with decent hand holds, and maneuvering their body to delicately place a foot on another foot hold, then slowly transferring weight over. But how often do you fall of a climb because you miss a foothold with your foot?

“Footwork” in climbing can also mean being comfortable standing on sloping, slippery or otherwise insecure feet; and also generating tension through your toes to drive your hips into the wall on overhanging terrain; and having mobility and core strength to use feet that are far to the side of your body; and toehoooks / heelhooks / kneebars / flags / kicks; and so on. Each of these presents unique dynamics - requiring novel movement strategies and coordinative structures.

Second, what is the ecology of a drill like this? If you’re on easy terrain, the information available to you is “pretty secure feet”. However, when climbers struggle with footwork it is mostly because they are getting very different information from their environment - feet that feel slippery and otherwise insecure. In a drill like this, we are not exposing ourselves to that sensory information, and therefore it’s unlikely that this will translate to that sort of situation.

“Silent feet” is just one instance of what I would call the “fundamentals” theory of skill development, which I think is common in the climbing community. The logic of it goes something like this:

you isolate a specific element of movement

you repeat that specific element many, many times on easy terrain

your body absorbs this movement, and it becomes automatic

this automaticity will generalize to a broader range of movements and harder terrain In alignment with this theory, a lot of climbers spend their skill development time on drills that follow this pattern - repetitive movement performed on easy terrain. Hopefully by this point it’s clear that ED has some conflicts with this model of skill development.

The Constraints-Led Approach

So what should we do instead? The method informed by ED is called the ***constraints-led approach ***(CLA), though I think a more appropriate name may be “guided exploration”, since “constraint” here is a scientific term that has some undesirable associations with the lay term.

The general idea is that the coach manipulates the environment, the task, or the athlete in order to encourage the athlete to explore new parts of the movement space - to self-organize in novel ways.

Self-organization and Learning

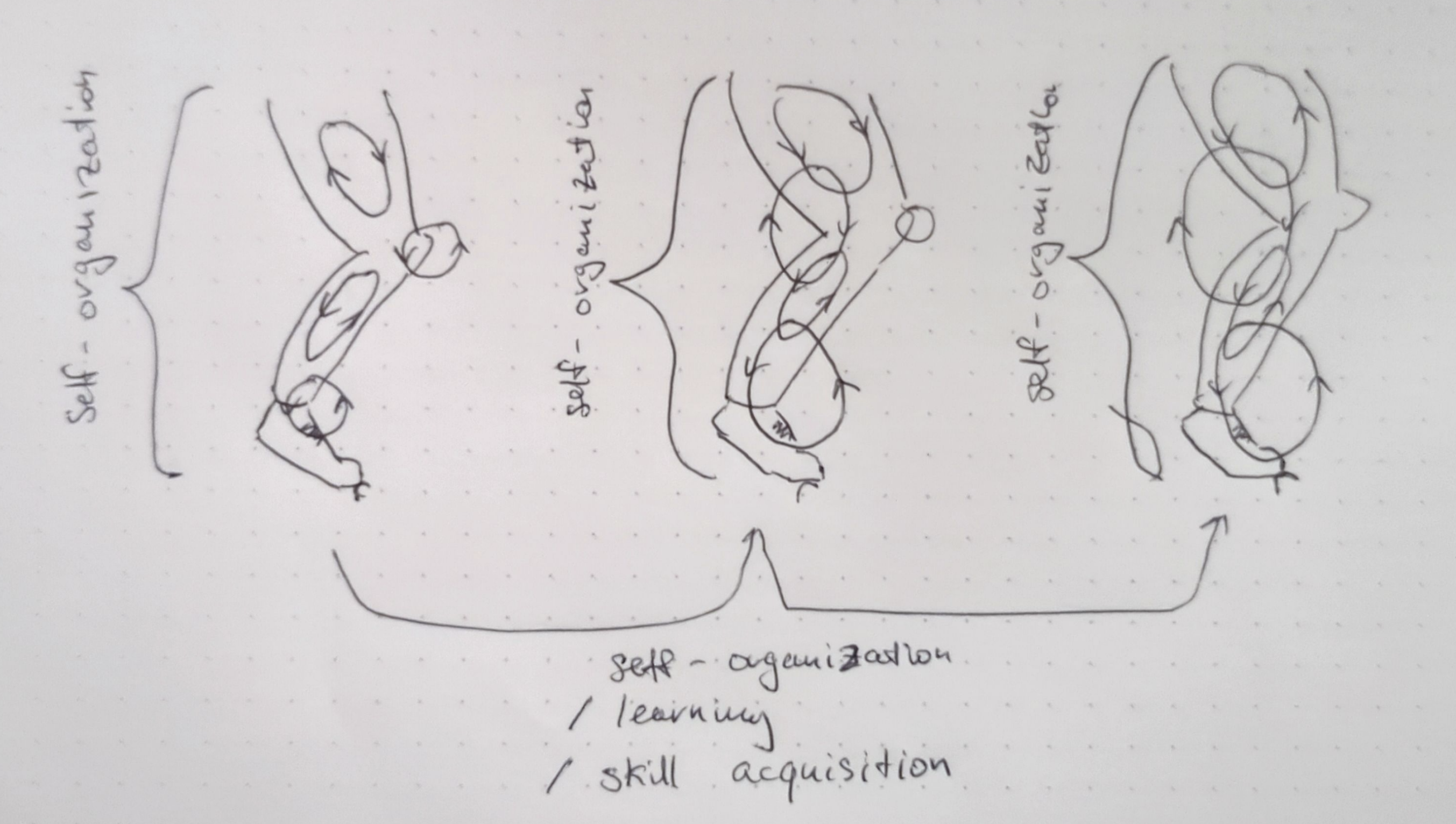

When I think about self-organization I actually think about a process happening at various timescales and levels.

Immediately, it is the way that your body moves. When you go to stand up on a slippery foot hold, the various components of your body coordinate with each other in order to make that movement happen. This is your body self-organizing in order to navigate the physical space - the space of forces and various joint angles.

As you keep climbing and stand on a variety of footholds in many different ways, your body becomes more efficient at solving this movement problem. Certain couplings become streamlined and more likely to arise. You becomes attuned to certain sensory information from the environment, and learn to ignore others. I think of this process of learning as your body self-organizing in a second-order space of movement strategies.

Each time you stand on a foothold, your body self-organizes to perform the movement. As time passes, the various muscle synergies and soft assemblies (represented as loops) adapt to become better at self-organizing. I think of this learning process also as self-organization, but on a longer time-scale.

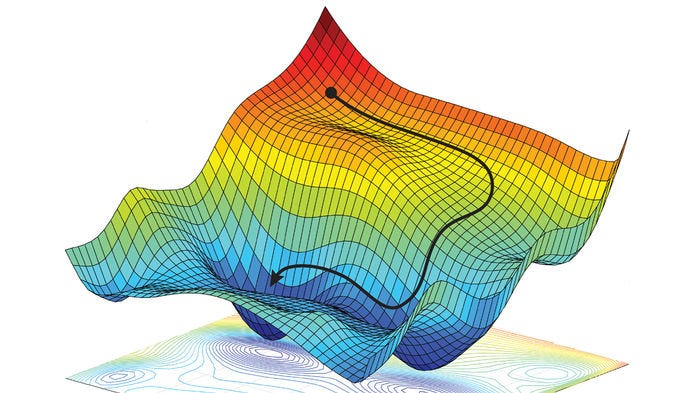

The position of the marble in the horizontal space is representative of the movement strategy. For example, the strength of certain muscle synergies. The height of the surface is how efficient the movement strategy is (lower is more efficient). Self-organization is the process of the marble rolling down the hill into the nearest well.

I imagine this movement strategy space as a high-dimensional surface - like a mountainous terrain filled with peaks, valleys and wells. The lower you are in the terrain, the more efficient and robust your movement strategy is. As you practice climbing, you are like a marble rolling around this surface. I see self-organization within this space as akin to gravity - pulling you down into the wells; adjusting your movement strategy to be more efficient and robust.

Within this mental model, arranging the athlete into the desired position, or prescribing a particular movement is like trying to balance a marble on an incline - as soon as you let go, the marble rolls back into the well, and the climber returns to their default movement strategy.

Instead, the goal of CLA is to perturb the landscape. Can we change the task, the athlete or the environment in some way that forces the marble to pop out of the well and explore more of the movement strategy space, so it has an opportunity to find new, deeper wells?

CLA in climbing

So how do we create an environment that forces athletes to elicit novel movement strategies? I think in climbing there is one obvious answer: setting!

In the process of diving into this topic, I discovered that I was already familiar with one practitioner of the CLA in climbing - Udo Neumann, aka udini. Udo was the national coach for the German bouldering team, coaching internationally successful athletes like Jan Hojer, and Juliane Wurm. Udo’s communication style is a bit… free-associative and hard to follow at times, but I thought his interviews on the Lebenspraxis podcast was the most straightforward entry point to his coaching philosophy. (I also think having an understanding of ED and CLA really helps one make sense of what the heck is going on in his videos. I definitely think his youtube channel is filled with hidden gems.).

In the interview, Udo shared some of his coaching process with the national team, and it has a lot to do with route-setting. He describes a close collaboration between the athletes, the coaches and the setters at the gym. Every practice, the setters and coaches would observe the athletes, identify movement strategies that they wanted to establish, and then set new boulders, targeted at each athlete, for next practice. Katsuaki Miyazawa, Tamoa Narasaki’s coach, seems to follow a similar approach.

Here are some videos demonstrating what a CLA practice might look like for teaching athletes to move on volumes.

I think it’s important to highlight a few aspects of this practice:

Rather than repeating the same movement, the athletes are exposed to a variety of sensory information and movement problems. As soon as athletes get used to a particular movement, the task or the environment changes. First the volumes are fixed on the floor, then they are allowed to slide. First the athletes can hop on top, then they have to run across, or use only one leg. As they are able to run-and-jump on a fairly big volume, they switch to a less positive one, and eventually a zero-tex one. They run up at different angles and jump to different holds.

The practice is designed around self-organization. The environment and the task demand novel movement strategies from the athletes. Furthermore, there is no prescribed movement. Instead, they are allowed to experiment and discover movement strategies that work for them.

Applications

Another frequently repeated line in the Perception and Action podcast is - it’s not enough to learn about the theories, you have to go out and try and apply them! Using the CLA requires constant experimentation and adjustment, and it’s not something you can theorize your way through.

Also, readers may be a bit disappointed by where we’ve come so far. OK, so pro athletes get custom route setting under the watchful eye of their coach, but how does that help me? Here are some ways in which I’ve applied ED and the CLA to my own climbing.

Finding Opportunities for Skill Work

I think the interview with Katsu Miazawa that I mentioned above gave me a pretty good idea about how to work on skills in a commercially set gym - seek out climbs that you have to power through, or where particular moves feel uncomfortable or awkward. Katsu says that when his athletes encounter a move like that, he changes the holds on the problem so the athlete can’t get away with an inefficient solution. Obviously you can’t really do that in a commercial climbing gym, so instead I use self-imposed constraints. “I have to use this foot”. “I have to use this beta”. “I’m not allowed to pull hard on this incut hold” (sometimes I just use one or two fingers on the hold, or avoid using the best part of the hold).

I am also being a lot more thoughtful about how I pick climbs to work on. Instead of constantly chasing the new set, or narrowing down on only a few grades that are at my project level, I think a lot more about the movement that the problem requires. “Does this movement feel awkward for me?” If so, I can adjust the difficulty with constraints to always stay at the boundary of what I can do, to force myself to move in novel ways.

As a concrete example, I currently climb around V7-V8 at my gym, but there was a V3 that I climbed during a warmup that felt really uncomfortable to me. It was on vertical terrain and had sloping, slippery feet. The first time I climbed it I felt like my feet would slide out if I stood directly on them, so my hips came out from the wall to make them feel more secure. This in turn meant that I was relying a lot more on my finger strength and upper body to support my weight.

I repeated the problem several times with different constraints - removing the most positive handholds, using just my back 2 fingers on each hand hold, letting go of both hands during each move. These were all constraints that forced me to actually put my weight on the feet. Once I got a feel for that, I repeated the problem a few more times, timing myself and trying to climb it faster and faster. This forced me to step on the feet with more confidence.

High-Quality Setting

I think this is also somewhere where the quality of the setting can really have a big impact. In this interview with Udo, he talks about setting. In particular, he says that when you put a positive hold on the wall, it really opens up the movement options. A strong climber can pull really hard on the hold and get away with poor positioning. On the other hand, by using flat directional holds you can constrain the total set of positions that are available even for very strong people.

Skilled setters can do this even at lower grades - forcing good positioning without requiring a lot of strength.

Unfortunately, in most commercial gyms where I’ve climbed, the lower grades were set with jugs.

Variety and letting go of “fundamentals”

Rather than doing drills or focusing a ton on repeating movements or boulder problems, these days I think a lot more about exposing my body to variety. I’m trying to climb boulders using multiple different betas. I’ve been taking the time to drive to the second-nearest gym more frequently, to expose myself to different setters and hold sets. I’ve been spending more time on the system board and doing more volume outside.

Another thing that makes a difference here is hold density. Say you find a boulder that has a movement that feels awkward to you. If the density at your gym is higher, you can substitute adjacent holds to get several variants on that same move. I guess this is also why spray walls and system boards are such a powerful tool for developing climbing technique - you can get a lot of variation and challenge levels around a particular movement.

Overall I’m really excited about further developing my coaching (and self coaching) by being creative on the wall and coming up with problem variations and constraints.

Future Directions

ED advocates against prescribing specific movements, but in CLA we are guiding the athlete to particular areas of the solution space. How do we pick the parts of the solution space we want to guide the athlete to? Isn’t that the same thing as prescribing a particular movement pattern?

The physics involved in the sport, and the common aspects of human anatomy make certain movement strategies more efficient and less injury-prone than others. For example, if you’re a swimmer, your speed will depend on how much drag your body creates. Therefore, it’s important to work on keeping your head down when breathing to minimize drag. If you’re a baseball player, the amount of force you can put into a pitch or into a bat swing will depend on how effectively you can transfer ground force into torque. So we should encourage the athlete to hinge, even if the CLA says that we shouldn’t prescribe when to hinge or at what angle.

Within ED these are the attractors of the movement strategy space. So what are such attractors in climbing?

One idea that Udo talks about a lot is proximal-to-distal vs distal-to-proximal movement. He claims that for many climbers, the intuitive thing is to go distal-to-proximal. That is, to start the movement distal (away from the center of mass), by pulling with the hand and then have the shoulders and hips (proximal to the center of mass) follow. Udo encourages athletes to also develop proximal-to-distal movement - to start the movement with the hips, and then have the shoulders and pulling follow that. He thinks this is one of the major reasons for Tomoa’s success [ref].

Another potential attractor has to do with falling and commitment. I think this is a relatable experience for many climbers: you are on a boulder move with a high heel. You wind up for the move and throw for an even higher hold. However, before you quite get there, your body involuntarily lets go of the heel, so that your feet are under you just in case you fall. If you had continued pushing through your feet, you probably would have stuck the move, so by preparing to fall you actually sabotaged yourself. Udo says that this lack of commitment is something many athletes struggle with, even at the world-class level [ref].

Perhaps a third example of an attractor has to do with standing on your feet - being comfortable pushing your hips into the wall and trusting that your feet won’t slip, rather than relying on upper body strength. When applied dynamically I think this resonates with Ross Fulkerson’s “making time over feet” concept.

I’m still pretty early in my thinking surrounding this, but I am excited to explore it further. I mentioned earlier that the concept of “footwork” can be broken down into many different techniques, each seemingly requiring a separate drill. Can attractors help us decompose climbing skill into larger, more cohesive units? Can we come up with ways to identify shortcomings in these attractors, and develop constraints for improving them?

I really think this is the future of skill development in climbing.

Against being dogmatic

If you search for discussions of the CLA online, you’re likely to stumble across Brazillian Jiu Jitsu communities. And in those communities you will see a lot of polarization surrounding the application of ED and CLA to the sport. Greg Souders popularized CLA in BJJ, and has been critical of traditional coaching methods.

In the surrounding discussions, people have a tendency to over-generalize and become more and more extreme and uncompromising in their positions. As a result, there is a lot of confusion and misconceptions about what CLA actually says.

I can totally understand how this sort of thing happens. Being a climber is a big part of my identity. I want to feel like I’m going about it the right way. A new idea like ED/CLA is really exciting, so it’s easy to get carried away, especially when it seems to contradict common wisdom.

I want to return to the example of the coach telling a climber to position themselves a certain way on the wall. One might find themselves thinking “you should never tell an athlete anything” or “that approach is useless”. However, do consider that language in itself can be a constraint that can encourage an athlete to explore a new movement. Self-organization is always happening - even during repetitive, isolated drills. Sometimes it is easiest to just tell someone to straighten their elbow.

(Consider also that a person’s beliefs around climbing are a dynamical system, and if you agree with the CLA you should also try and apply it to that situation. If you are telling someone they are wrong about something they are doing, perhaps you too are guilty of using an ineffective language constraint. [ref])

ED/CLA doesn’t say that we should never use these methods. Instead, I think CLA warns us that these methods may not work in certain situations, and gives us some ideas about what to do next. I really hope the climbing community doesn’t go the way of BJJ when it comes to CLA. Please don’t use CLA/ED as a club to hit people with.

CLA all the things

ED is a nuanced and interconnected set of ideas and I really struggled with how to put it into a linear narrative. There are many more things that I wanted to include, but decided to leave for future posts. Consider subscribing to the newsletter or following the rss feed if you want to read those.

One last thing that I wanted to share is that learning about Ecological Dynamics has really changed the way that I see the world. Dynamical systems are everywhere - emotions and cognition, relationships, teams, organizations. I have found the concepts of self-organization and attractors immensely useful in gaining a deeper understanding into many parts of my life, and have been applying the ideas of the Constraints-Led Approach both at work and in my personal life.

I’m already writing a post about applying ED and CLA to organizations, software teams and software development.

Thank you for reading to the end! This blog post took a ton of time and effort and I hope you enjoyed it. If you did, please let me know via email or on mastodon. It’s really encouraging and helps me write more. And I really love thinking and talking about this stuff!

Till next time!