Book Review: The Sports Gene

What the book is about

Are athletes born, or forged through practice and effort? The answer frequently given to this question is “both”. But this answer is unsatisfying - an evasion. Certainly, it’s both, but is it 50-50? 80-20? 99-1? What are the mechanisms through which an athlete’s genes impact their performance? Can unsuitable genetics be overcome with heart, a love for the sport, and skill developed through a lifetime of practice?

David Epstein tackles these questions in his book, the Sports Gene. Epstein talks about directly observable traits like height and arm length for pro basketball players, or the hip width and leg length of sprinters and endurance runners. He drills into more nuanced aspects of our athletic hardware: visual acuity, muscle fiber composition, tendon sizes, attachment points, and blood oxygenation.

Even traits that we typically attribute to practice are built on the foundation of our genes. Our genes influence the ability of our muscles to recover, grow and strengthen, and the ability of our nervous system to learn and adapt to new movement patterns - in short, “trainability”.

Indeed, nothing is sacred in this book. In a chapter about dogsled racing, Epstein talks of huskies that are bred to love pulling the sled, suggesting that our drive to engage in a sport is influenced by our genetic blueprint.

Through stories of famous “naturals” like Donald Thomas, discussions of the genetic mechanisms and ambiguities of gender, and dissections of the improbable over-representation of athletes of certain genetic lineage in various sports, Epstein makes the case that it is our genetics that dictate the level of achievement we can expect in a sport.

So this is what the book is actually about, and I encourage you to read it to see if the arguments presented are convincing.

What the book was about for me

For me, the experience of reading the book wasn’t really about the story of the emerging genetic science. Rather, what I found the most interesting were the hints about a second layer to this story: how is the emerging genetic science undermining the meaning people place in athletic performance, and how are people reacting to this new reality?

Discipline, character, consistency, heart, will-power, drive, hard work. These are the things people associate with performance, both in sport and in other aspects of life. These are the stories that surround achievement and give it meaning. The team won because they wanted it more. The athlete is the best in the world because of their uncompromising work ethic.

Epstein starts the book with a discussion of the 10,000 hours myth - the idea that anyone can become an expert at anything given 10,000 hours of practice. Epstein points out that the myth is based on a misinterpretation of an exploratory observational study, dealing with the amount of practice that musicians self-reportedly required to get to an elite level. There was a huge amount of variance within the initial study - some musicians become elite after a mere 2,000 hours, and some only after 20,000. I don’t think that it’s a leap to acknowledge that there are some people who never get to an elite level even after a lifetime of practice.

One has to marvel at how widespread the myth has become despite being based on such flimsy evidence; and how tenaciously it persists, despite efforts from scientists to correct the record.

From The Sports Gene,

The “practice only” narrative … has an obvious attraction: it appeals to our hope that anything is possible with the right environment, and that children are lumps of clay with infinite athletic malleability. In short, it has the strongest possible self-help angle and it preserves more free will than any alternative explanation. Sports scientists who do genetic work occasionally told me that their research has a public relations problem stemming from the idea that genes are rigidly deterministic, and that they negate free will or the ability to improve one’s athletic station… genes, however, are not biological destiny, but simply tilt one’s physical predispositions. Unfortunately, that moderate message is often entirely lost in a mainstream press that heralds each study of a new gene as if it completely supplants some aspect of human agency.

Jason Gulbin, the physiologist who worked on Australia’s Olympic skeleton experiment, says that the word “genetics” has become so taboo in his talent-identification field that “we actively changed our language here around genetic work that we’re doing from ‘genetics’ to ‘molecular biology and protein synthesis’. It was, literally, ‘Don’t mention the g-word.’ Any research proposals we put in, we don’t mention the genetics if we can help it. It’s: ‘Oh, well if you’re doing molecular biology and protein synthesis, well, that’s all right.’” Never mind that it’s the same thing.

Another passage from the Epilogue,

Consider this title and subtitle of a Sports Illustrated story: “The Fire Inside: Bulls center Joakim Noah doesn’t have the incandescent talent of his NBA brethren. But he brings to the game an equally powerful gift.” The “gift” is Noah’s desire to win. Never mind that he is the 6’11” son of a French Open tennis champion and has a wingspan of 7’1.25” and a 37.5” vertical jump. If those aren’t incandescent athletic endowments, then what, pray tell, are? Noah’s lack of talent referenced in the headline - and by Noah himself in the story - would seem to describe the fact that he’s a graceless ball handler and mediocre jump shooter. Which, based on the sports science, probably has to do with the specific work he has put in to develop dribbling and shooting skills than with his hereditary gifts. A more honest headline might read: “The Talent Outside: Joakim Noah has not acquired basketball-specific skills to the extent of his teammates, but he is at the upper extreme of humanity in terms of his physical gifts and therefore can be a good NBA player anyway.”

People want to believe that they are in control of their own future. If you try hard enough, if you want it bad enough, then you can achieve whatever you set your mind to. Consequently, in this world view, you can find great meaning in your struggles and accomplishments. For many it becomes a central pillar of their identity.

That identity is challenged when faced with evidence that a significant part of one’s achievements can be attributed to their genes - a gift, a privilege. Nobody likes that. So they pretend that the science doesn’t exist, and uncritically consume and propagate a world view of overcoming any obstacle through hard work.

Genetics in Climbing

Climbing is my sport of choice, and I think it’s an interesting case study of this particular dissonance. First, let’s consider the sport from a genetic point of view.

Climbing is dependent on one’s body proportions - their strength to weight ratio, and also on the distribution of the weight in the body (To oversimplify, you don’t see a lot of high-level climbers with tiny shoulders and massive hamstrings).

Climbing relies on one’s ability to position one’s body in space - balance, proprioception, coordination and timing.

Climbing is a mental sport, requiring one to overcome their fear of heights to perform complex movements while at risk of falling.

Something that I think makes climbing fairly unique is that it significantly stresses the fingers - a complex and delicate structure that climbers use in a way not selected for by evolution. (Our ancestors did not live or die by their ability to climb cliffs while hanging on to 10mm edges, as far as I know).

I believe that in all of these regards, and the fingers especially, it’s likely that some people are going to find their bodies far better equipped to excel at climbing than others.

Consider a brief thought experiment. Say your finger tendons have more advantageous insertion points, and your pulleys are relatively thick. It’s likely that you can push yourself a lot harder and progress in finger strength a lot faster, relative to someone with less suitable fingers who may struggle with recurring injury. Suppose you generally have coarse, dry skin. The extra friction will make you feel more secure on the wall, and allow you to explore a wider range of movement possibilities. If you happen to be endowed with an alacritous nervous system, you will absorb these new movement possibilities much quicker than another person might.

Indeed, some kids skyrocket into double-digit boulders over the course of a couple of years, while others would consider climbing a V10 a lifetime achievement.

Climbing culture

So what of climbing culture? In my experience, climbing culture is deeply into the “hard work” world view.

Climbers are obsessed with getting better at climbing, to the point that overtraining is a common issue, as are eating disorders. Online climbing communities are preoccupied with the question of optimizing your performance. Which finger training protocol is most optimal? Should you lose weight or try to get stronger? Should you train off the wall or just climb?

Much of the media that surrounds training for climbing is permeated with a tough-love attitude. Not getting where you want to be? You’re not trying hard enough. You need to commit. You’re not being honest with yourself about your weaknesses. Mind over matter.

I’m going to call out climbstrong here. I actually really like their training advise and am a big fan, and I certainly don’t think they’re uniquely egregious in this respect (one doesn’t have to search far to find tough-love in sports writing). I think this particular case is relevant because I actually read The Sports Gene based on a recommendation from their newsletter:

David Epstein's book, The Sports Gene, is a fascinating read. He dives deep into nature versus nurture, the genetics of specific cultures, and gives us a good idea on when to quit blaming our parents and start looking at our behaviors.

When I went back to find that quote I had to do a double take. Did we read the same book?!

The other edge of the sword

From The Sports Gene,

Several sports psychologists I interviewed told me that they publicly support a view that marginalizes genes because they believe it sends a positive social message. “But maybe it’s dangerous too”, one eminent sports psychologist told me, “to say that you’re stuck where you are because you’re not working hard”

Why do people cling to the 10,000 hours myth? Why do they react so defensively when the “hard work” world-view is challenged?

I believe that behind most defensiveness is an insecurity - a wound. And I think this wound is actually caused by the other edge of the same proverbial sword. If achievement is a direct consequence of hard work, then what happens when you reach the limits of your achievement? The flip side of “you can overcome anything with hard work” is that when you meet something you cannot overcome, it is because you aren’t working hard enough. You don’t want it bad enough. The limits of your achievement become character flaws.

Many readers of this article are probably here because they followed my efforts to get better at climbing. Maybe you are on a similar journey. What I didn’t write about in that journal - what I don’t think many people want to talk about, is the way that this tough-love mentality can easily turn into something worse.

When I can’t seem to make any improvement after years of training, tough-love turns into negative self talk - I’m not disciplined. I’m not committed. I’m not smart enough to figure this out. I’m not trying hard enough.

It sours my relationship with climbing, sapping the joy out of doing an interesting problem. It entices me to push to the point where I’m constantly injured and in pain. It undermines my sense of self-love in this and other aspects of my life.

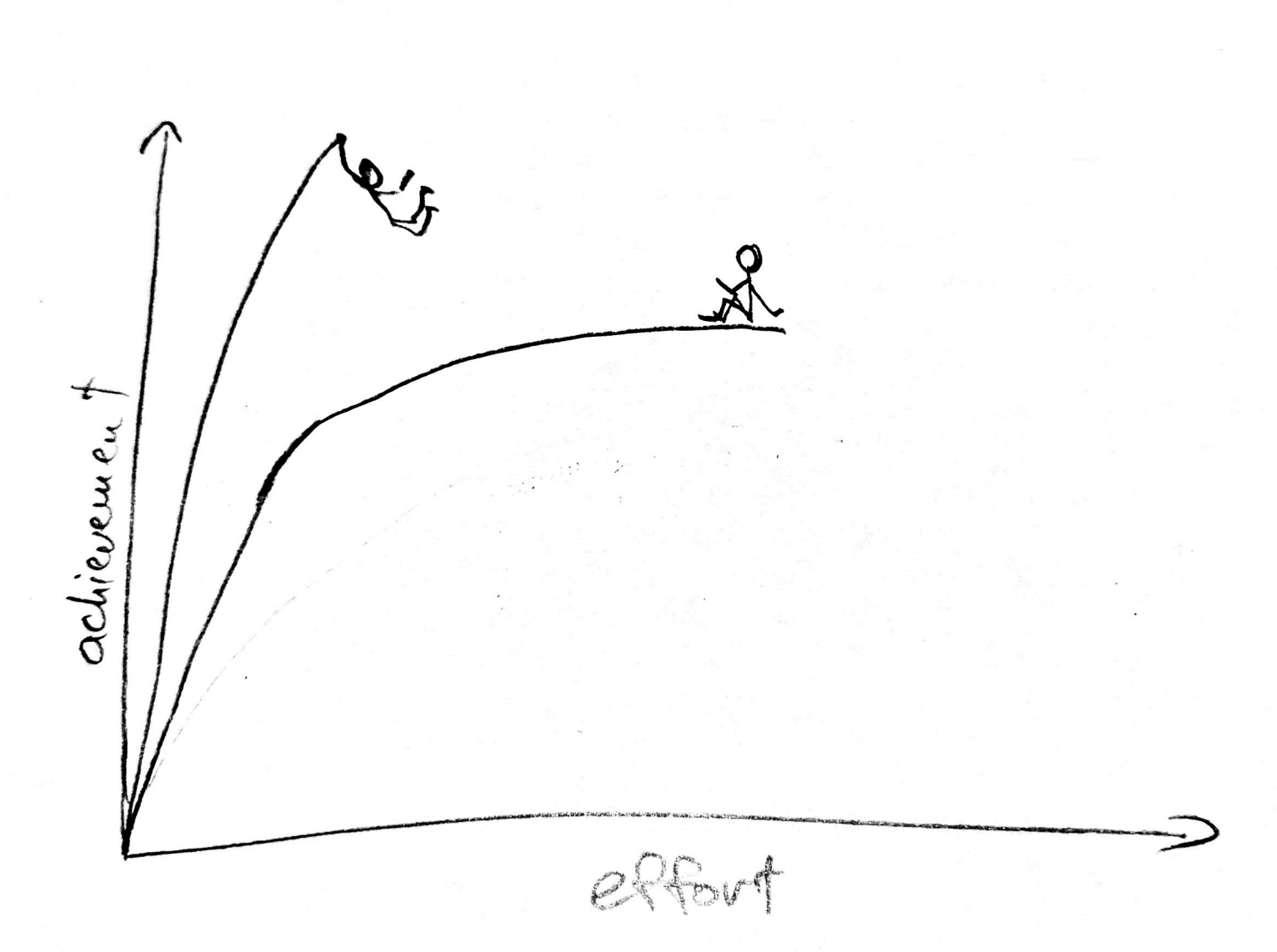

From this point of view, I found The Sports Gene very therapeutic. Maybe I’m OK. Maybe I pushed myself a good way up my own achievement curve, and for me it’s pretty darn tough to climb at my current level.

As a brief aside, a common retort when talking about cultural issues is to push the responsibility to the individual. People will say “comparison is the thief of joy”, or “just stop caring what other people think”. To this, I will counter - humans are social creatures.

Have you ever tried to find a place to sit in a crowded cafeteria? I imagine you can relate to the gamut of emotion that might accompany such an inconsequential situation. So is it any wonder that we are heavily influenced by the culture of our friend group, our gym, our crag, our online communities?

As humans, we need to feel like we are valued in the spaces that we inhabit. Our sense of meaning is largely constructed upon our relationships with the people that surround us.

Towards a new climbing culture

So how can we account for our emerging understanding of genes, and the role that chance plays in absolute levels of achievement? What else can we value, when we know that sometimes greatness is possible without hard work, and hard work doesn’t always lead to greatness?

First off, I feel like I have to acknowledge that while effort won’t necessarily make you better than another person, effort certainly can help you improve relative to where you currently are. And I do feel like there’s a lot to be said about tackling your weaknesses, applying yourself, and finding your own limits. However, I am wary of the siren song of self-improvement, as I feel like it can easily transition into self-flaggelation. For those who go down this path, remember that pain is not the unit of effort.

climbing as a creative act

I’ve been really enjoying training for climbing as problem-solving - an expression of creativity, curiosity and experimentation. It’s been a way to connect with the idiosyncrasies of my own body, and explore my own style of climbing. I may not be able to do a double-digit boulder, but I still find it interesting to figure out how to apply myself to solving specific movement problem. The various techniques that I can discover and apply to the problem are fascinating, and I feel a sense of accomplishment when I can figure it out.

I’m also trying to be aware of people’s individual differences, and to admire the various ways in which people adapt their climbing styles to their own bodies. This means being up-front about the relative advantages and disadvantages that various bodies present. I think we all would be a lot happier if we could look at a novice, heavier climber navigating their way through a V3 and admire the courage, creativity and skill involved to the same degree as a young phenom cruising a V11.

climbing as a way to connect

Climbing can be a shared challenge that can bring you together with the people around you. It can be an obsession that you can share with others.

I’m trying to ask more people about their climbing journeys. What brought them to climbing? Why do they like it? How does it make them feel?

I’m trying to be present and enjoy the ups and downs of working a problem with a group of people, and also, to enjoy the people themselves - their personalities, and the way that each person contributes to the moment.

I like climbing media about humans. I really enjoy videos about people attempting wacky challenges and just having a good time together, enjoying each-others company.

And beyond

The Sports Gene made me reflect on my life in another way. How do the topics covered in this essay translate to the rest of our society? While I don’t have the climbing gene, I definitely have the math/computer-science gene. I attended some of the most selective educational institutions in the US, and they certainly brand themselves as having the most hard-working students, rather than the most genetically fortunate.

What genetic qualities predispose one to be successful in a particular field, and how are those fields compensated? Did software engineers earn their substantial paychecks because they worked harder than everyone else, or are they just winners of a genetic lottery that makes it easier for them to hold a certain kind of abstraction in their minds?

I think another reason people react so negatively to talk of genetics in sport performance is that the values of individualism, self-determination and meritocracy are fundamental to propping up capitalism. One can justify vast wealth inequality and exploitation if you veil it in the morality of hard work.

So now we get to the core of this essay - a critique of capitalism veiled in a reflection on climbing culture, veiled in a review of a book about genetics. I hope you enjoyed our journey together.

If you struggle with being extremely self-critical about your sport, or other aspects of your life, I think you should pick up this book. I think you’ll find the read therapeutic, as I did.